- Home

- Catherine Bateson

Rain May and Captain Daniel

Rain May and Captain Daniel Read online

RAIN MAY

AND

CAPTAIN DANIEL

Catherine Bateson grew up in a secondhand bookshop in Brisbane — an ideal childhood for a writer. She has written two collections of poetry and two verse novels for young adults, A Dangerous Girl and its sequel, The Year It All Happened. Her first prose novel, Painted Love Letters, was published in 2002 and shortlisted in 2003 for CBCA Book of the Year Awards Older Readers and the Ethel Turner Prize in the New South Wales Premier’s Awards. Catherine lives in Central Victoria with her two children, a dog and a cat. Her son’s favourite Star Trek character is Data and her daughter’s is Seven of Nine. Catherine has taught creative writing for over a decade and particularly likes conducting writing workshops in schools.

Poetry

The Vigilant Heart

For Young Adults

A Dangerous Girl

The Year It All Happened

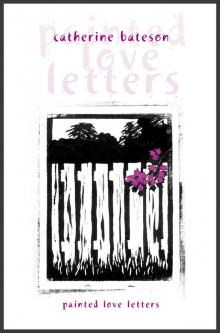

Painted Love Letters

The Air Dancer of Glass

CONTENTS

Author biography

Also by Catherine Bateson

Title page

Praise for Rain May and Captain Daniel

Moving to Boringsville

The Dream House Countdown

City Weekend

Drips, Bullies and Mr Beatty's Platypus

Hearts and Hurts

Aliens Everywhere

Trekkies Rule!

Imprint Page

PRAISE FOR

RAIN MAY AND CAPTAIN DANIEL

Told with such finesse … The characters are related with economy and acute perception, the dialogue is excellent. A wonderful little book.

Reading Time

With deft strokes, Bateson fashions characters of substance … Characters resonate with authenticity. Highly recommended as a novel for younger readers.

Jane Connolly, Magpies

This is a rich exploration of the challenges of change, delving into issues of loyalty and friendship with a positive outcome. Moving and entertaining.

Laurine Croasdale

Primary English Teacher Association Newsletter

Bateson has created a wonderful message to give to all 11- to 13-year olds

Lyndon Riggall, The Examiner

A book that is warm, gentle and positive, and describes a friendship that is never mawkish and is ultimately about loyalty.

Alexa Dretzkais, Readings Hawthorn

Moving to Boringsville

When Dad moved out of our home and into Julia’s apartment, Mum changed her name to Maggie, put our house up for sale and had a huge clean-out. I didn’t mind the first and last things so much, but I hated the idea of selling our house.

‘We have to sell, chickadee,’ Mum said. ‘It’s the settlement arrangement your father and I made. Anyway, I don’t want to live here. We need a fresh start. We’re going to live in Granny’s old house.’

‘But that’s in the country. We can’t move to the country.’

‘It’s perfect timing, really — the tenant who was there has handed in his notice. He’s moving to Tasmania for the landscapes,’ Mum said as though she hadn’t heard me.

‘I don’t understand. Why?’

‘He’s an artist. Apparently he wants to paint in Tasmania.’

‘No Mum, Maggie — I mean, why do we have to move? What about school? What about my friends?’

‘You’ll have a new school.’

‘But it’s halfway through the year. I can’t change now.’

‘You’ll have to,’ Mum said. ‘I’m sorry, Rain, but that’s all there is to it.’

‘I won’t know anyone. And the country! Bor-ingsville.’

‘Well, that’s exactly one of the reasons I think we should move,’ Maggie said. ‘The country is the only place one can stand still for long enough to hear your own heartbeat. I’m sick of this rushing. I rush in the morning to get everything ready to begin a day of rushing. I rush home in the evening to get to bed early enough to start all over again the next day. And what have we to show for it? A bookshelf full of self-help books on achieving a stress-free life and a credit card debt. It’s time for a new life, Rain.’

I hoped the house wouldn’t sell. I refused to clean up my bedroom, and when the agent showed people through, I made sure that the rug in the lounge room was askew so they could see the burn in the carpet underneath and I complained loudly about the water pressure, the neighbours’ cats and the traffic noise. No one paid any attention. People commented instead on all the things I loved about the house — the ceiling rose in the lounge room, the neat kitchen with its breakfast nook, the fig tree in the backyard.

After people had walked through our house and touched the walls and paced out the size of the rooms, Maggie and I would walk up to the shops and buy fish and chips and eat them in front of the television without saying anything.

The house was sold to a couple. He wore a pin-stripe suit and she wore bright lipstick and I hated them because they sighed when they saw the concrete backyard and rolled their eyes at the old stove in the kitchen and tutted about the toilet being in the bathroom rather than separate. Maggie didn’t care.

‘It’s their house now,’ she said, ‘or will be on settlement date. And we’ll be starting a new life, Rain, in a new house.’

‘An old one,’ I pointed out, ‘and run down. You said so yourself.’

I like having the last word.

As soon as the contract was signed, Mum started the Big Clean Out.

‘I’m simplifying my life,’ she said, flinging clothes into op shop bags, emptying drawers and stacking box after box of paper for recycling. ‘No more stuff for the sake of it. Everything must be useful or beautiful.’

She threw out things I didn’t know we had, like an old black and white television set, some zoo-print curtains — unfinished — a whole lot of old vinyl records and a tennis trophy my father had overlooked in his move. I watched as she piled it all in the back of the car for the op shop and I knew I should have rescued the tennis trophy and given it to Dad next time I saw him, but I didn’t. I just watched it go off to the op shop with the rest of the junk.

Maggie was all glittery and brittle the day of the move. She spoke to the removalists in a thin voice that tried to be jolly. She asked them things about schools in the area, what the weather was like now, the state of rural health funding and how they liked living in Clarkson.

The young guy just mumbled into his Blundstones, but his father grunted out replies while he heaved our boxes and wardrobes.

‘School’s good,’ he said, ‘small — about sixty odd. My three went there. When Jeff went through there weren’t even sixty, were there? Bloody cold, but. What’s your heating like?’

‘Wood fire,’ Maggie said. ‘I suppose it still works. I honestly haven’t seen the place for a few years — not since we cleared it out after my mother died. We’ve had tenants in it.’

‘Yes — that artist bloke. He kept it quite well — did a bit of gardening. You’ll have to get someone in to check your chimney flues, make sure they’re all right. Order some wood in — I don’t think he will have left you any — didn’t seem to do much cooking. Ate at the pub most nights.’

‘Is there someone local to look at the flues?’ Maggie sounded less jolly.

‘Oh sure. I’ll give Mick a hoy, he’ll do it for you. Get him on the phone, Jeff, tell him to check out the flues in the old Carr place and drop round some wood at the same time.’

Jeff mumbled and ducked out to the truck.

‘You needn’t worry about rural health.’ Jeff’s dad laughed. ‘You’re living right next to the doctor.’

‘Oh, that’s useful,’ Maggie said in an undecided way. After the

removalist left, Fran, Mum’s best friend, came over and helped us say goodbye to the house. I went through room by room promising them I would never forget them. Mum and Fran hugged a lot, then Fran cried and Mum put on her sunglasses and we drove off. Just drove off.

‘Don’t look back,’ Mum said. But I did and I saw Fran waving her hankie as though we were going on a long, long journey.

‘The great thing about starting afresh,’ Maggie said, putting her foot on the accelerator to emphasise her words, ‘is that you get this wonderful chance to reinvent yourself, to become the person you want to be. Who do you want to be, Rain? It’s your choice, darling — anyone in the world.’

I thought about it. Seriously, what I would like to do is to dye my hair a far-out galaxy blue, pierce my ears five times, right up to their pixie tips, and wear a lot of black, or purple, or orange. I’d like to be positively brilliant at one thing — designing houses or painting pictures or writing science fiction stories. And I’d like to have a wild bedroom with a dark blue ceiling and the whole of the milky way painted on it in glow-in-the-dark paint. I’d like to be a little mysterious and have my whole grade talking about me, half-scared of my cleverness and sarcasm, but I’d also like one special friend. We’d swear eternal love and when we had daughters we’d call them after each other so they’d grow up special friends, too.

Maggie wanted to practise serenity and harmony. She was giving up executive stress and office politics. She didn’t even want to be on the School Council. She wanted to meditate for an hour a day, do yoga and rediscover her creative self. She wanted to find herself a place in a small community. She wanted to chill out for a couple of years, grow vegetables and plant her feet firmly on the earth.

‘I’ll leave the stress and office politics to your father and Julia,’ she said. ‘They can worry about money and investments and getting to the top of the food chain. I’m sick of it. I want a real life you can measure by heartbeats, not in debit and credit columns.’

I didn’t understand quite what she was talking about. If she meant my father had been obsessed by money, she was wrong. He might be obsessed by work, I’d give her that — but not money. Dad hands out money like it’s tissues and never asks for the change back.

I didn’t want her to get on to what went wrong between her and Dad, so I started humming something which could have been a song from the Acid Indigo or might, on the other hand, have been from Circus Ponies. I wasn’t quite sure myself, but it was nice and loud and made my lips and the inside of my nose tingle.

‘Well,’ Maggie said, getting the hint after a minute of humming, ‘well, won’t it be fabulous settling all our stuff in a new house. And think of the backyard, Rain — it’s such a beautiful space for a child. We’ll be able to plan a really wonderful garden there with secret places and little meditation spots and it will be quite magical. I always felt terribly sorry for you in that poky narrow Brunswick garden.’

Actually I loved our Brunswick garden. Yes, most of it was concrete, but that was great for rollerblading and scootering. I loved the cherry tomatoes Mum had planted in my old plastic swimming pool and, even though you couldn’t climb it, I loved the big fig tree out the back. In fact, the more I thought about it, the more our old backyard had going for it: the rosemary bush, for example, the leaves of which were delicious with roast potatoes and lamb, and the grape-vine which regularly produced bunches of grapes each summer. It hurt me that someone else was going to enjoy such bounty every year.

‘Granny’s garden is twice as big,’ Maggie interrupted as though she had read my mind, ‘so there’s twice as much space to do things. And don’t you remember the wonderful apples we’d harvest from her trees when you were little? And the damson plums, too — every year, branches drooping to the ground heavy with fruit. Mum would make jam, damson cheese and plum sauce.’

I remembered Granny quite well. Her face was all soft, like flower petals. I remembered stroking it when she had a headache. And sleeping with her in her bed when Mum and I would visit and how she would smell musty, like op shops and old books. I’d wake her up in the morning and she’d have to put her false teeth in before she went out to make breakfast but she’d talk to me without them and her words would be all blurred. She would tell me stories about when she was a little girl. She was chased through a paddock by a bull once and only escaped because her cousin Harry hauled her through a gap in the fence by her frilly knickers.

‘I miss her,’ Maggie said. ‘I miss knowing she’s up here. I think that’s when it all started with your father and me, after Mother died. People dying, your mother dying, makes you think about how you are living.’

I could see how Maggie would miss Granny and I thought I did too, a bit. It’s funny — I don’t miss Dad the way I thought I would. I thought I’d miss him all the time. Instead I’ve become used to talking to him on the phone. And then sometimes I miss him so sharply it’s like an ice-cream headache, the sort you get when you eat really cold ice-cream on a hot day. I miss hearing him come home after work and I miss hearing them talking at night. I miss Sunday mornings when he would cook great big breakfasts of pancakes, bacon or banana fritters. Now, when I’m over at his new place, we go out for breakfast. Julia likes to do that. She’s latte dependent, she says. The juice is always good but you never get quite enough bacon, I reckon. And it’s a bit dippy, sitting out where everyone can see you having breakfast.

‘Coming into Clarkson,’ Mum said, interrupting my thoughts, ‘weather crisp, no air turbulence. Oh, look, they’ve got a new Welcome to Clarkson sign up.’

‘Wineries,’ I read on the big green sign, ‘craft, galleries. Gosh, it doesn’t look as though there’s room for all that.’

‘Darling, there’s the school.’

It was just a school. I refused to be impressed.

‘Cruising down the main drag of Clarkson,’ Maggie said.

‘Right Mum, there’s a newsagency, a baker — watch that dog!’ A beagle dawdled across the road and Mum had to stop.

‘A kind of gallery,’ I said, looking out my side, and ‘there’s a shop with a lot of stuff in the window, teddy bears and stuff.’

‘There’s a Thai restaurant,’ Maggie said. ‘Hallelujah, Rain — a Thai restaurant!’

‘And a pub,’ I said. ‘And what’s that huge place on the corner?’

‘A Bed and Breakfast,’ Mum said, ‘and a bar — well, Clarkson has expanded.’

‘It’s hardly Chadstone shopping centre,’ I said.

‘Still, a Thai restaurant. And look, that must be the doctor’s place, behind the hedge, and here we are.’

Mum got out of the car and stood with her hands on her hips. ‘Needs painting. Definitely needs painting. These cottages scrub up well with a paint job. Look at Granny’s roses, Rain — they’ll make a beautiful show in summer.’

‘Great.’

It was dark inside the house and cold. Both the lounge room and the kitchen were dark and dingy. The bedrooms were better — quite large and with windows that looked out on to the garden.

‘Your choice,’ Maggie said. ‘Which one would you like?’

‘This one,’ I said, choosing the smallest one, closest to the kitchen, ‘I want this one.’

‘Are you sure you don’t want the bigger one? What about your desk?’

‘Can’t I have a study in the room next door?’ I asked. ‘This room?’

‘Oh, yes — that’s where Granny used to work,’ Maggie said. ‘It’s a lovely warm room, Rain — and look, the plum trees. And spring bulbs coming up, too.’

The house meandered out the back into a large room which had been built on to the original cottage.

‘What will we do here?’ I asked. ‘It’s weird, Mum — like a second living room or something.’

‘I think it was a family room, originally, ’ Mum called out from the kitchen. ‘Granny lived down there in winter — don’t you remember reading beside her? Oh god, that’s what he meant by getting wood in and cooking.

’

‘What?’

‘Mother had a slow combustion stove. I had completely forgotten. I nagged and nagged at her to get a proper stove but she wouldn’t. Well, chickadee, it’s pizza tonight.’

‘What? There isn’t a stove?’ I was shocked.

‘There’s a wood stove, a slow combustion stove.’ Maggie sounded tired.

‘How do you cook on that?’

We looked at it. It was a large stove but it didn’t look as though it would ever work.

‘I don’t know, really,’ Maggie said. ‘I mean, you put the wood in, obviously, and there are controls to regulate the heat somehow. Mother used to say that nothing cooked bread or soup as well as a slow combustion cooker. I’ll have to look it up on the Internet, or ask someone.’

She pulled open the oven door and peered in.

‘It doesn’t look very clean,’ she muttered. ‘Oh yuck. I think that’s mouse poo.’

‘Gross. Forget it, I’m not eating anything cooked in that.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ Mum stood up and glared at me. ‘It just needs cleaning.’

‘Everything needs cleaning,’ I said. ‘Everything looks dirty. Even the walls.’

‘Shh, isn’t that the truck?’ Maggie said. ‘Go out and have a look, Rain.’

Even our furniture didn’t make the house seem brighter.

‘Just needs some paint,’ Jeff’s father said. ‘You’ll get it right, Mrs Carr. A lick of paint and you won’t know the place.’

‘There’s only a slow combustion cooker,’ Mum said.

‘With mouse poo in the oven,’ I said.

‘A good clean out, that’s all that needs. There’s nothing like these cookers. And this one isn’t that old. I remember the old lady, sorry, I mean your mum, pulling the other one out. This one would be, let’s see — she got it a couple of years before she died. They last a lifetime. The old one would have, too. I told her that but she wanted a new one. A fancier one. Look, this one’s even got a wok burner. She was proud of that. A great one for cooking, your mum, not like some of these pensioners living on dog food. She’d cook up a nice little meal for herself every night, flowers on the table, the whole bit. People thought she was a bit queer, but I always say live and let live if you’re not hurting anyone else.’

The Wish Pony

The Wish Pony Millie and the Night Heron

Millie and the Night Heron Magenta McPhee

Magenta McPhee Painted Love Letters

Painted Love Letters Mimi and the Blue Slave

Mimi and the Blue Slave Lisette's Paris Notebook

Lisette's Paris Notebook Rain May and Captain Daniel

Rain May and Captain Daniel