- Home

- Catherine Bateson

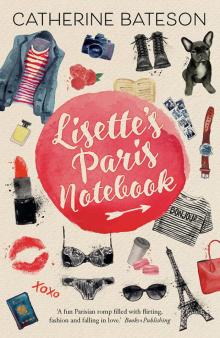

Lisette's Paris Notebook

Lisette's Paris Notebook Read online

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published by Allen & Unwin in 2017

Copyright © Catherine Bateson, 2017

The moral right of Catherine Bateson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the United Kingdom’s Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Allen & Unwin – UK

Ormond House, 26–27 Boswell Street,

London WC1N 3JZ, UK

Phone: +44 (0) 20 8785 5995

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.murdochbooks.co.uk

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia: www.trove.nla.gov.au. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (AUS) 9781760293635

ISBN (UK) 9781743369562

eISBN 9781952535819

Cover and text design by Debra Billson

Cover images by Hanna Bobrova, Anna Kozlenko/123RF, and Nancy White/Shutterstock Internal images by DeAssuncao_Creation/Shutterstock, moloko88 and Anna Kozlenko/123RF, and Nancy White/Shutterstock

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

For Helen – her summer book, at last!

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Author’s Note

About the Author

What do you wear to Paris? Ami and I discussed it for hours but I still couldn’t think of anything suitable. Ami said a trench coat with nothing underneath but your best underwear. That was only if some boy was meeting you at the airport, I said.

By the time I landed in Paris, the anger that had burned with wildfire intensity during the first leg of the journey was a pile of hot ashes somewhere between my heart and my stomach, right around where my Vivienne-circa-1970s-inspired tartan kilt strained against the airline food, popping open the smallest safety pin. Anger was replaced by the equally uncomfortable emotion of fear.

Would I be able to understand anything? How did the airport train work? Where was my apartment? What the hell was I doing in Paris?

But I knew what the hell I was doing in Paris and that sailed me through the passport check, the baggage claim and on to the RER platform without faltering. It carried me right past the suburbs, which were like ugly suburbs anywhere, to the correct station, up the stairs lugging my suitcase and out into Paris proper. Paris and Notre-Dame!

‘Oh my God!’ I said, and then corrected myself, ‘Oh mon Dieu!’

Until that moment I had not believed in Paris. It was a city that existed in movies, Vogue magazines, my French teacher’s memories and my mother’s imagination. I’d read about it, I’d seen it once removed, I’d even talked about it in French conversation classes. I took three steadying breaths, shouldered my backpack and grasped my suitcase handle more firmly. This was my city for the summer. This was where I would conquer my fears and remake myself. I’d arrived a caterpillar – okay, a caterpillar in plaid and safety pins – but I would transform into a butterfly. I hoped.

I walked across the bridges (the Seine! a barge decked out as a tourist boat! pale stone and orange shutters!) and past a square, nervously checking my map as I went, and wishing I’d allowed myself some data coverage. Google Maps – I missed it already! Some of the smaller streets just weren’t on my flimsy piece of paper. My sense of direction, which worked in the Southern Hemisphere, had gone on strike in Europe. (Europe!) My suitcase bumped and wobbled over the cobblestones. (Cobblestones!)

I found my street, which was really an alley, purely by accident, and by that time my suitcase wheels were complaining. I walked past the back doors of cafes and restaurants and the kitchen staff, idly smoking, checked me out. I tugged at my tartan skirt. Probably should have put that zip in: the safety pins didn’t feel secure enough for Paris. Paris! My heart did a little extra thump just for that word. Soon I’d be sipping café au lait at the front of one of those cafes, I promised myself, not skulking past the dishies on their smoke-o.

Further along the street a young woman scooped up water from the gutter to wash her face. She had such bad bed hair that it was matted in thick dreads at the back. I tried not to stare at her. I gripped my suitcase tightly and strode past her and her bundle of belongings. She was only slightly older than me and living in a doorway. That wasn’t the Paris of old movies.

My building, however, was and seeing it in real life lifted my heart again. It was six storeys high and each window was decorated with its own box of flowers. On the ground floor was the shop, La Librairie Occulte, owned by Madame Christophe, my mother’s clairvoyant and my landlady – concierge? – for the summer.

I peered through the window. It was just like any bookshop catering for weirdo mystics. There were salt lamps, crystals and piles of incense. All the signs were in French, although some boasted a small English translation for the tourists. In a corner of the room there was a woman working on a laptop. I pushed open the door, setting chimes ringing, and squeezed between the bookcases and display cabinets. Sweat had begun to bead on my forehead and I knew the stale airline food smell clung to my clothes. I’d left Melbourne in tartan-and-tights-weather and arrived in Paris on an early summer day.

‘Bonjour, Madame,’ I said in my best French accent. ‘I’m Lise.’ Back home, I’d been Lisi despite being christened Lisette by my romantic Francophile mother. In Paris I’d be Lise, silent ‘e’ and more sophisticated. It was my bon voyage present to myself.

‘I have expected you,’ the woman said. She shut the laptop and lifted the smallest dog in the world from her lap and tucked it under one arm. When she stood up I could see that she was wearing a charcoal grey sleeveless shift, more Chanel than clairvoyant, and a scarf that changed from ruby red to dark purple, depending on where the light caught it. She came from behind the desk to air kiss each of my cheeks and I could smell expensive perfume, rather than incense. She was perfectly balanced on stilettos and even the wrinkles on her face were designer.

‘You must take after your father,’ she said, holding me at arm’s length. ‘Your mother is quite round, yes? With curls? Your father is

tall and fair, yes?’

Up until only a while ago I would not have been able to answer that question. For years my mother had acted almost as though I’d been immaculately conceived – but now my backpack contained four photos of my father and yes, I was definitely his daughter. I nodded.

‘Welcome to Paris, Lisette.’

‘Actually, I’m called Lise.’

‘In Paris you will be Lisette. This is Napoléon. Come, I will show you the apartment.’

I didn’t have time to even pat the dog before Madame Christophe popped him in his basket, clipped out a back door and then smartly up five floors of steps. I dragged my suitcase behind her, panting, until we reached the very top. Madame Christophe flung the door open. ‘Voilà!’

I’d expected some kind of kitchen and a balcony with a proper table and two chairs. There would be a view of the Eiffel Tower, the Sacré-Cœur or something else iconic. I didn’t even have a balcony. I stood in the smallest ‘apartment’ in the world. It was effectively one room with a kind of kitchen annexe. I pushed past the bed and opened one of the windows. The air was still and hot. I looked up and down the narrow street. If I stood on tiptoe I could just glimpse the Seine. That was something.

‘I will leave you to make yourself comfortable,’ Madame Christophe said sternly. ‘The bathroom is on the landing. Practically an ensuite. You will share it with no one as everyone is in the South.’ She turned on her heel and clipped back down the stairs.

Apart from an ugly chest of drawers and the bed, the apartment was empty, which was a good thing in one way as there wasn’t room for anything else. Where was the antique four-poster bed, the heavy wardrobe I’d imagined filling, and the washbasin stand?

I unpacked my suitcase and slid it under the bed. Apart from my 1970s Westwood tartan phase, I’d also embraced a kind of grungy seventies aesthetic based on op-shopping, upcycling and some of my own sewing. When I had first agreed to go to Paris, Mum had been really excited. She’d studied the latest issues of French Vogue, sketched designs and looked at fabric samples. She is the seamstress, I just sew. She’d wanted a whole upmarket hippy look – wafty cream silks, pale linen wide-legged trousers as far from my old fisherman’s trousers as oysters are from battered flake.

‘But everyone wears that kind of stuff,’ I’d said, stabbing my finger at a perfectly beautiful maxi dress that was, the caption told us, ‘mousseline de soie incrustée de dentelle’, which translates as unbelievably expensive.

‘Hardly,’ Mum said, ‘not at that price!’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘I’m not offering French lace, Lisette. Just something more . . . elegant and grown-up?’

I was all dress-ups – I could hardly escape fashion, living with a seamstress, but I’d wanted my own spin on it. In the end, I’d let her help me make a maxi skirt. I’d imagined a fabric with a sugar-skull pattern but we’d negotiated on tissue-thin gauzy stuff instead, subtly patterned with tiny skulls. It was almost too cool but Mum talked me into it. She also insisted on lining the skirt to just below my knees. I felt like a proper adult when I swished into my next French class to show it off.

‘Isn’t it perfect?’ I asked Madame Desnois.

‘You will feel alien,’ she prophesised. ‘It is more London than Paris. The French are more chic than’ – she searched for an adequate word – ‘punk.’

‘This is high-class punk,’ I explained, ‘this is punk couture.’

Now, leaning out the window into the heat, I wondered if I shouldn’t have made just one white or cream top. Why hadn’t I packed sandals? It was just too hard to think of summer in the Melbourne winter and I hadn’t wanted to listen to Mum’s advice at that point. My French boy would buy me clothes. He’d dress me up to meet his parents who’d live in the country somewhere smelling of lavender. His parents would be charmed by my skull theme and his father would pour me a vin ordinaire and teach me to roll my ‘r’s the way Madame Desnois wanted.

I tested the bed. My feet stuck over the edge. The pillow was a long sausage that squished flat as soon as my head touched it. I’ll just close my eyes for a few minutes, I promised myself. Just five minutes.

I stayed there, drifting in and out of consciousness, the sounds from the street wafting up through the window, until someone called up the stairwell, ‘Lisette! Lisette! À table!’

‘Some French girl,’ I thought sleepily. ‘There’s another girl up here. That’s nice.’ Then I woke up properly and remembered that Lisette was me, I was Lisette.

I followed the smell of coffee to a small room that was Madame Christophe’s living room. A round table in one corner had been set for two. The plunger coffee was strong and served with long-life milk. The baguette had some kind of good, nutty cheese balanced on top of ham, a smear of mustard and a decent slather of butter. I wasn’t hungry but hunger wasn’t necessary. I ate my portion and crusty crumbs flew over the lace tablecloth. Madame Christophe sipped her coffee and looked away. I could hear myself chewing.

‘You must walk,’ she said when I’d finished.

‘Walk?’ I was still exhausted and my stomach was full. The dog was asleep in his basket and I wanted to curl up, just like him. My eyes felt scratchy with invisible grit. I’d been awake for nearly twenty hours straight if you didn’t count cat naps. Couldn’t walking wait?

‘Walk,’ she repeated. ‘You must walk until dinnertime, then you come back and eat, if you can, and go to bed. It is necessary to defeat the jet lag.’

‘I’m tired now,’ I said, but Madame Christophe ignored me and cleared away the crockery.

I trudged back up all the flights of stairs to get my backpack and camera and then all the way back down.

‘You are not taking that?’ Madame Christophe eyed my canvas backpack.

‘Why not?’

‘It is like a tourist.’

‘Don’t French girls carry backpacks?’

‘Of course not. We have the handbag, the clutch or the pochette. And there are thieves.’

‘A thief couldn’t get into this,’ I said, pointing out the buckles.

‘But they do. They have the knives.’ Madame Christophe mimed a knife slicing the canvas straps.

‘It’s all I’ve got,’ I said. ‘I’ll be fine.’

‘You do not carry anything valuable?’ Madame Christophe said. ‘You have not your passport?’

‘Of course not.’

She shrugged in a resigned way and then pushed me out into the street. It was only after the door had closed that I remembered I had left my map behind. I could easily have gone back in, but Madame Christophe was watching me from near the tarot display. I stuck my head in the air, shouldered my backpack and set off walking in what I hoped was a good direction.

Everything was old. Everywhere I looked was another old building. It wasn’t even as though they were monuments, they were just buildings. I tried to memorise which way I’d gone but the streets curved and twisted and, at one point, I went down an alley and ended up back where I’d just been. Within fifteen minutes I had no idea which direction I’d started out from. I sat for a while in a square opposite an impressive building. It was the Hôtel de Ville – the Town Hall of Paris! – but I couldn’t stop myself from yawning.

‘Eavesdrop,’ Madame Desnois had advised. ‘Wherever you are, listen to the people. Of course, there are not so many French in Paris in summer, but you will still hear the language.’

I tried to eavesdrop, but it was too hard. The couple closest to me, both eating ice-creams, were definitely not French. There was an American woman with a couple of kids nagging her for McDonalds. An intense conversation between an older couple was in French – I caught isolated words – but it was too fast and private for me to follow. I sat there until I was in danger of falling asleep in the sun and then I started walking again.

Old buildings and old streets were great, but there were rules for walking in Paris that I didn’t know yet. You couldn’t stop and gawp or people ran into you.

You certainly couldn’t take photos or people muttered at you under their breath. You didn’t stare at the beggar with the cats on leads or he would hold out his hand for change you didn’t yet have. You certainly didn’t stop where the woman knelt on the pavement as though praying, her hands holding a small paper begging cup. Who could do that? On the dirty footpath? It was all utterly – and wonderfully – overwhelming.

Then I found the BHV, a huge department store with five levels of shopping, French style. Dogs shopping along with their owners! I tried to pat one and was snarled at by both it and its mistress.

‘There are rules of etiquette,’ I remembered Madame Desnois telling me anxiously. ‘Lisette, I don’t think you quite understand how formal the French can be.’

Apparently you needed an introduction before you patted someone’s dog. How was I going to survive twelve weeks without anyone, not even the dogs, talking to me? I started with the clothes. They were expensive, but so chic and French. Even though I was definitely not chic, in my cobbled-together kilt, maybe I would be by the time I left Paris? These clothes floated from their hangers, elegantly declaiming their desirability. Well, I’m here now, I thought, so I explored each floor of the BHV as though I was desperate for beach towels, new shoes, baby clothes, picture frames and even DIY tools, which I discovered in the basement. Despite the snarling dogs, the supercilious shop assistants and the other shoppers who ignored me, the store was a cocoon. I wasn’t jostled and no one begged for money. I’d have time to get used to the real Paris, I thought, when I was less tired, more confident and not wearing heavy Docs.

By the time I left the store it was late afternoon, although still very light. I walked out onto a different street and had no idea where I was. I should have taken photos with my phone of my directions, like Hansel and Gretel leaving crumbs in the fairytale. Around me was a surge of Parisians, all the women wearing high heels and scarves, all the men in designer crumpled linen and polished, beautiful shoes. I ended up on a larger street, near a group of food shops. Dinner. My stomach growled.

It would have to be classic for my first night in Paris. My first night in Paris, I repeated to myself, cheering up instantly. Goat’s cheese – I could say that to the shopkeeper and I did when he finally turned to me. Who knew there would be so many different kinds? I gave up trying to understand what he was saying and just pointed to a pretty pyramid, and then another wrapped in a grape leaf. I bought a supermarket baguette – it would do until I found a proper bakery – and I tried to ignore the mouth-watering smell of the rotisserie chicken. I wouldn’t be able to eat a whole one and I couldn’t remember how to say free-range in French.

The Wish Pony

The Wish Pony Millie and the Night Heron

Millie and the Night Heron Magenta McPhee

Magenta McPhee Painted Love Letters

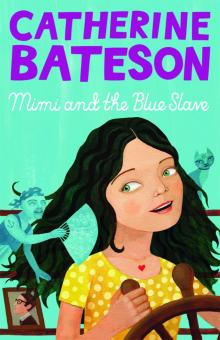

Painted Love Letters Mimi and the Blue Slave

Mimi and the Blue Slave Lisette's Paris Notebook

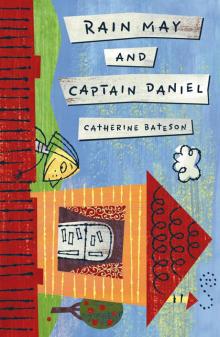

Lisette's Paris Notebook Rain May and Captain Daniel

Rain May and Captain Daniel